Reviewed by Grant McCreary on January 16th, 2016.

If you’re a birder, chances are you want to be a better birder, regardless of your current skill level. You’re not alone, which is why publishers continually print books purporting to help you in this pursuit. The latest on this subject is Better Birding: Tips, Tools, and Concepts for the Field.

Given this book’s title and, especially, subtitle, you are probably expecting it to cover general, although perhaps somewhat esoteric, topics that would help a birder to find and identify birds. Perhaps something similar to How to be a Better Birder, which covers such things as habitat, geography, and weather. But, with the exception of the introduction, that’s not what Better Birding delivers. Instead, it gives detailed identification information on hard-to-identify members of 24 groups of birds.

What bird groups are generally considered the trickiest to identify? Shorebirds and gulls, certainly. Definitely Empidonax flycatchers, those little winged devils. Many get tripped up by those “confusing fall warblers”. Yet, other than a small selection of shorebirds, none of these are included in Better Birding. This is a bit surprising, but the criteria the authors used to choose which groups to cover helps explain it:

(1) we thought the group represented a good opportunity to build core birding skills, (2) we thought the group could use a refreshed treatment, or (3) we thought the group was interesting and we wanted to present it using this format.

Better Birding covers the following groups, focusing on those members found in North America:

- Loons

- Swans

- Mallard and Monochromatic “Mallards”

- White Herons

- Eiders

- Brachyramphus Murrelets

- Pacific Cormorants

- Sulids: Northern Gannet and Boobies

- Tropical Terns

- Atlantic Gadflies

- Curlews

- Godwits

- Marsh Sparrows

- Small Wrens (Troglodytes and Cistothorus)

- Accipiters

- American Rosefinches

- Swifts

- Screech-Owls: An “Otus” and the Megascops

- Nighthawks

- Yellow-bellied Kingbirds

- Black Corvids: Crows and Ravens

- Pipits

- Longspurs

- Cowbirds

So it appears that a reason those infamously difficult groups weren’t included is that there are already one or more excellent specialty books covering them, with the exception of those pesky empids (where, oh where, is The Flycatcher Guide?). That’s perfectly valid. And some groups that were included have tended to be overlooked in books such as this. The wrens and marsh sparrows, for instance, gave me fits until I got some experience with them. And even now they can cause me problems if they are seen poorly (unfortunately, that’s how they’re usually seen). So I was very pleased that Armistead and Sullivan included them.

Are you surprised to find out what Better Birding actually includes? I know I was, and wondered if this book shouldn’t have a different name. But look back at the first selection criteria above, about “core birding skills”. As you read through various accounts here, you’ll learn not just identification tips for certain groups of birds, but how to see birds. In that, this book is more akin to Kaufman Field Guide to Advanced Birding than it is to How to be a Better Birder.

This emphasis is subtle. The authors don’t beat you over the head with any one approach. There is no “You must use GISS!” (or jizz, impression, etc), or “You’ll never amount to anything if you don’t bird by ear,” or anything of that sort. Instead, the authors stress various factors, as appropriate for the group they are discussing. For example, voice is seldom helpful in at-sea identification of petrels, but molt can be vital, whereas voice can be critical in differentiating between some nighthawks or kingbirds. As the authors put it:

Woven into each chapter are lessons that will help organize your thinking about a group of species, which in turn we hope will lead you to become more adept at finding, identifying, and knowing what you see in the field.

It is not usually necessary, or even advisable, to read a book like this cover to cover. Normally, you would just read the section of whichever groups you are interested in at the time. But to realize the full benefit of what the authors are doing here, you need to put in more effort. Each chapter consists of a short introduction, a list of “Hints and Considerations”, group-wide identification tips, and specific information for each of the species covered. I would recommend reading at least the first three sections of each and every chapter, which would provide not just general identification information for that group, but also a foundation for identifying any bird.

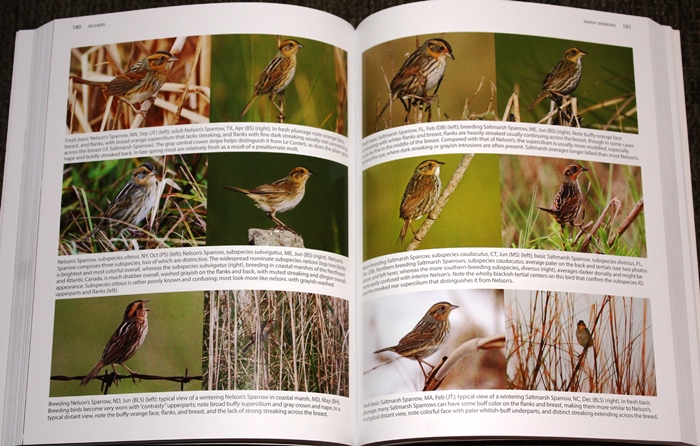

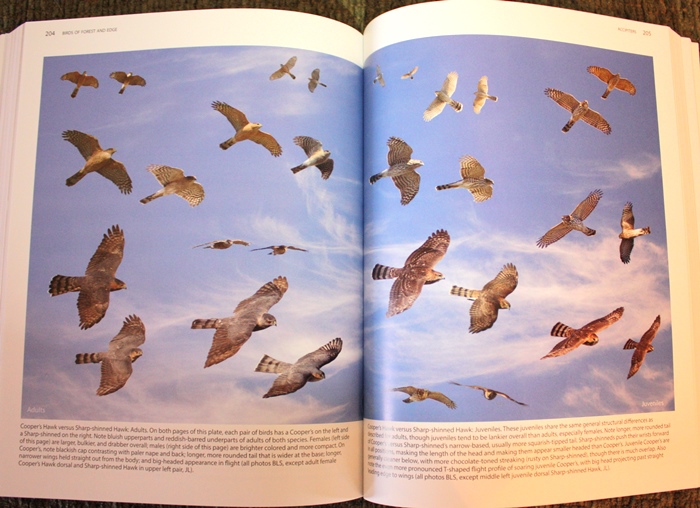

A great way to delve into more species-level identification is to read the photo captions. This isn’t to suggest that you completely ignore the text, but you could learn much, without getting bogged down in too many details, by simply paging through the book and reading every caption. It helps that the plates are extremely well designed. Except for a few scattered smaller images, each is a full page, containing either a single image or multiple rows of one or two photographs each. Generally, each plate deals with just one species, showing it in various plumages and postures. Care has been taken to show similar species in similar arrangements, making comparison between the two easier. For example, the female House Finch is the left image on the second row of one page, while a female Purple Finch is in the same spot on the opposite page. Both are perched up, facing right.

To compare species in flight, Armistead and Sullivan often use composite images. These also are carefully crafted to facilitate comparison. These digitally manipulated images look great and, more importantly, make it much easier to see differences between species.

A few photos have captions that do not identify the birds shown, allowing them to serve as review quizzes. Other books, most notably The Shorebird Guide, do likewise to great effect. The ones here would be similarly instructive if it weren’t for one thing – most of them don’t have answers anywhere to be found. Without that, these quiz photos lose their helpfulness.

While you’re going through and reading the accounts and captions, don’t ignore the sidebars. One or more of these, with notes on natural history or taxonomy, can be found in each grouping. I’m really glad to see an ID guide include such material, which may be only indirectly helpful in identification. Even so, I would argue that such knowledge is essential to becoming a better birder. It’s also fascinating! For example, we learn that:

- The white plumage of immature Little Blue Herons appears to allow them to closely associate with Snowy Egrets, which increases their feeding success. The Snowies, which will drive off the darker adult Little Blues, seem to tolerate these white birds, thus giving them a better chance at surviving while they are still learning how to fend for themselves.

- You may have noticed an illustration in your favorite field guide of a Whimbrel with a white back. You want to pay attention to it, as that is the Eurasian subspecies, which may be split. But as the authors note here, the “Eurasian Whimbrel” consists of three subspecies, two of which have been recorded in the ABA area. (All of these are shown nicely here in a great comparison plate.)

Mentioned last here, but the first thing you should read in the book, is the introduction. In 18 pages it covers general topics of use in improving your birding skills. First, it guides us on how to look at birds:

Identification is very much about identity, but too often our study of a species ends with the acquisition of a single signature field mark. A bird’s appearance is but one part of its identity. Expertise is gained only by looking at the bird as a whole. And the whole includes not just a bird’s plumage, shape, behavior, and flight style but also its habitat, seasonal habits, range, and natural history. Truly expert birders know not only what the bird is, but why the bird is.

It goes on to distribution, bird sounds, molt, and taxonomy. Those first two are not surprising; I think most birders understand that they are important. But molt and taxonomy are subjects that many shy away from, perhaps thinking they are too complicated. Armistead and Sullivan defuse any such objection. They give a clear, simple overview of these topics and make a compelling case that birders disregard them to their own detriment.

Recommendation

So will Better Birding: Tips, Tools, and Concepts for the Field actually help you to be a better birder? Yes, it certainly can. Intermediate birders, especially, will find it extremely useful. And anyone, experts included, should get it if it covers a group you’d like help with. I hope to see even more bird groups getting similar coverage in Better Birding 2!

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

[…] Our own Events Manager George Armistead has a new book out, and Grant McCreary at The Birder’s Library is a fan. […]

[…] The Birder’s Library […]

I like this book.