Reviewed by Grant McCreary on February 26th, 2015.

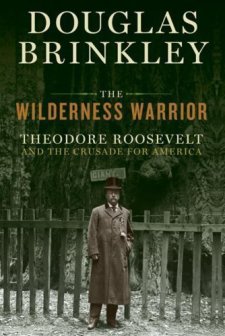

I’ve long admired Theodore Roosevelt. He was, after all, an honest-to-God birder. And, of course, he was instrumental in the National Park movement. But, other than his leadership of the Rough Riders and place on Mt. Rushmore, I really didn’t know much about him. I wanted to rectify that, but was disappointed to find that none of his numerous biographies seemed to focus on what I was most interested in – his legacy of conservation. So I was thrilled when The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America was published in 2009. It looked like it could be the exact book that I’d been longing for. After finally making time to read it, I found that assessment was right on.

The Wilderness Warrior is a traditional biography in its more-or-less chronological treatment of Roosevelt’s life. But Brinkley deviates from most other biographies by focusing on one particular aspect – T.R. as a naturalist and conservationist. Thus, the reader is told about Roosevelt’s birth and childhood, but there is less about his circumstances and family life than there is about his burgeoning love of nature. Similarly, the “big” moments of his life, such as his involvement in the Spanish-American War and ascension to the presidency, are included, but his views on the need to preserve America’s forests get much more attention. And Brinkley doesn’t even describe the circumstances of Roosevelt’s death, choosing to end his narrative shortly after T.R. leaves the White House.

But, as readily apparent by the sheer size of this book, there is still plenty to include. A review like this can’t adequately summarize 800+ pages of relatively small type, so I’ll just mention some of my favorite parts. Foremost is learning that T.R. not only loved birds (I think most of us already know that), but he could be considered a hard-core birder. Before he even graduated from college he had written two books on bird distribution (the Adirondacks and around his family home on Long Island). Brinkley mentions multiple times that those accompanying T.R. on one of his many forays marveled at his ability to identify birds, especially by sound. A few of Roosevelt’s birding trips were covered in some detail, but only through college (afterward his trips were mostly focused on game and large mammals). Birds, however, remained a constant thread throughout his life.

You may be familiar with the creation of the first Federal Bird Reservation of Pelican Island. At that time, the demand for bird feathers to adorn ladies’ hats was so great that many species of wading birds were in danger of being wiped out. Every breeding season their rookeries were scenes of carnage. One such rookery was Pelican Island, on Florida’s Atlantic Coast. Frank Chapman, the most prominent ornithologist of the day, and others beseeched Roosevelt to do something to protect the island. Brinkley describes the scene:

After listening attentively to their description of Pelican Island’s quandary, and sickened by the update on the plumers’ slaughter for millinery ornaments, Roosevelt asked, “Is there any law that will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a Federal Bird Reservation?” The answer was a decided “No”; the island, after all, was federal property. “Very well then,” Roosevelt said with marvelous quickness. “I So Declare It.”

Thus was created the first unit of what would become the present-day U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Refuge system. That may be one of the most well-known actions that T.R. took to protect our country’s wildlife and land, but it was far from the only one. All told, during Roosevelt’s presidency six national parks, 18 national monuments, 51 Federal Bird Reservations (many of which became National Wildlife Refuges), and 150 national forests (created or enlarged) were established. This is nearly unfathomable:

In seven years and sixty-nine days, Roosevelt had saved more than 234 million acres of American wilderness. History still hasn’t caught up with the long-term magnitude of his achievement.

Brinkley is unapologetic in his praise for Roosevelt (well-deserved, in my opinion), but he doesn’t shy away from pointing out character flaws and seeming inconsistencies in his actions and policies. The most obvious of which is that he loved animals and wanted to protect them, but he was also an enthusiastic hunter (some might go so far as to say blood-thirsty, especially earlier in his life). Brinkley is able to reconcile these two facets, for the most part, and present a possible rationale to explain Roosevelt’s contradictory attitudes.

There’s a fine line between thorough and tedious. Brinkley walks that line with the skill of a tight-rope walker. At times he includes too many insignificant details, such as the car number of the runaway trolley that once slammed into Roosevelt’s carriage (injuring him and killing a Secret Service agent). He also gives biographical details – sometimes brief, sometimes not so brief – of the many people that come into Roosevelt’s circle. Many of these will be familiar, like Frank Chapman, John Muir, and John Burroughs. But others, such as the first refuge manager of the Pelican Island sanctuary, are more obscure, but no less interesting. Each reader will have their own opinion on which side of the spectrum the author falls, but if you have any interest in the subject you’ll likely come down on the positive side.

Given the large role that birds play in this story, the book could have used a read-through from a real birder to catch mistakes like “red-bellied nuthatch”, “sharp-skinned hawk”, and the photo caption that misidentifies guillemots as cormorants. And there are other things that birders are likely to pick up on, such as when Brinkley quotes T.R. about “little snowbirds (clad in black with white waist coats)” and notes that he was probably referring to Snow Buntings, when it’s more likely he meant Dark-eyed Juncos. Brinkley also seems to have misinterpreted the concept of micro-evolution.

On the plus side, it is mind-blowing to read about America-that-was, with its ecosystems and bird life intact (relative to today, anyway). The forests still held Passenger Pigeons (barely, if that, at the end – T.R. reported a small flock in 1907, after the last confirmed sighting), the Louisiana canebreaks still had Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. Oh, to have accompanied Roosevelt on one of his trips to the Dakota prairie or New England forests!

Recommendation

I’ve long admired Theodore Roosevelt. Now, after reading The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, he’s my hero. It is no exaggeration that America would be very different place – a much poorer one – without him. Brinkley’s biography is fascinating reading, all the more so if you share Roosevelt’s love of birds or the National Parks.

Roosevelt was a pro-forest, pro-buffalo, cougar-infatuated, socialistic land conservationist who had been trained at Harvard as a Darwinian-Huxleyite zoologist and now believed that the moral implications of On the Origin of Species needed to be embraced by public policy. The GOP was in trouble.

Oh, that it were again.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Comment