Reviewed by Grant McCreary on February 9th, 2013.

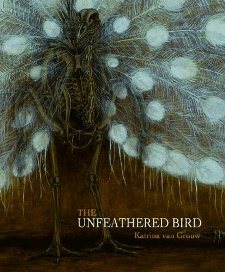

Begun over 25 years ago, Katrina van Grouw intended this book to be a primer on bird anatomy for artists. But the scope and purpose eventually morphed into The Unfeathered Bird, which has to be the most unlikely bird book that I’ve ever seen. It is a large, coffee-table-format book filled with exquisite artwork, gorgeously presented. But that art is of bird skeletons or even, literally, skinned birds. The text delves into bird anatomy and physiology, yet does so in a way that is not only understandable to non-professionals, but actually interesting and relevant to birders. The author describes this unique result as “a convergence of art and science; accessibility and erudition; old and new”.

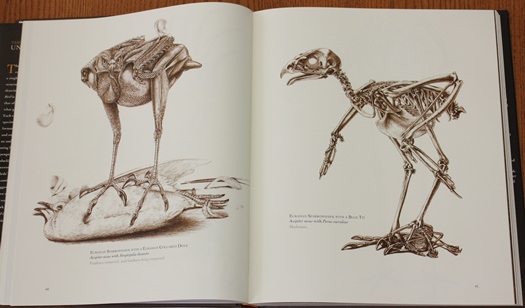

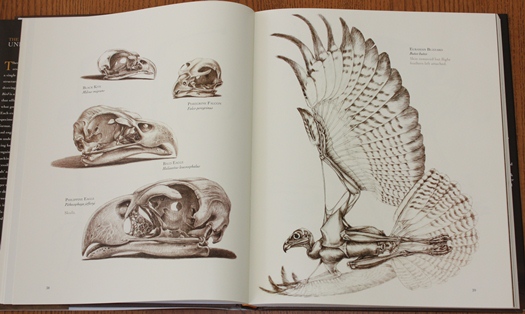

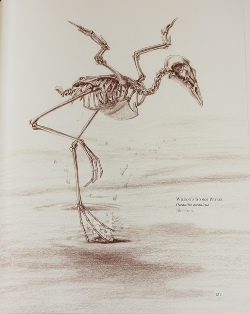

van Grouw’s artwork, which graces virtually every page, is a paradox. She shows some birds without feathers so that the skin is visible, and others without both feathers and skin so that you can see the muscles. But most often her drawings are of just the bird’s skeleton. And yet, her birds look alive! This is because she illustrates them engaging in natural behavior: loons swimming as if underwater; Eurasian Sparrowhawks with prey; a frigatebird pursuing a tropicbird. This is in stark contrast to anything you would find in an ornithology textbook. The result is that the drawings here are actually interesting, which invites appreciation and careful investigation. The author/artist cites Audubon as an influence, and the similarities are easy to see.

The art is also, in a weird and perhaps macabre sense, really beautiful. I never thought that bird skulls could be made attractive, but van Grouw found a way. This is all the more surprising as photographs of the same subjects would be grisly at best and in some cases downright gruesome. And not nearly as compelling. This is certainly one case where drawings trump photos.

If this were just about internal anatomy, it would be of interest to a very small audience despite the fantastic artwork. As much as I love birds, I have no interest in reading a bird anatomy textbook. So I was glad to find that while you do learn about such things as the pygostyle (the last vertebrae that are fused together to form a base for the tail), there is much more to this book than that. As van Grouw writes, “in fact, this is really a book about the outside of birds. About how their appearance, posture, and behavior influence, and are influenced by, their internal structure.” So she doesn’t just state that, for example, storm-petrels have long “hands” relative to their arms while albatrosses are just the opposite, she relates that fact to their lifestyle and how one impacts the other. I probably shouldn’t have been, but I was surprised by how many behavioral traits are due to, or enabled by, anatomy. For instance, have you ever wondered how toucans, which aren’t small birds, can fit inside their tree cavity nests? They’re able to flip their tail up and forward to save space.

Here are just a few of the more interesting things I learned from The Unfeathered Bird:

- Toucans are remarkably poor flyers despite their large wings.

- The “intimidating glare” of birds of prey is largely caused by overhanging “eyebrows”, formed by bony plates protruding from the skull that may serve to protect the eyes while pursuing prey.

- When eating a long snake, kingfishers sometimes have to wait, with the tail dangling from its bill, while the head end is digested.

- Using wings to both fly and swim is a compromise, and restricts the size of the birds: “It’s no coincidence that the largest of the flying auks – the Guillemot [Common Murre] – is about the same size as the smallest of the penguins.”

- Gannets have shallow grooves running along the length of the bill, which “may function as sighting lines to aid in accurately targeting prey”.

- Skimmers are the only birds to have vertical pupils.

Still, interesting facts aside, this is a book about bird anatomy written by a former museum curator. It has to be boring, right? Wrong! Ok, so the introductory chapters can be a little tough to get through (but very important to read, as they help to understand what follows). But the family accounts are great, although they are still best read a few at a time at most, in order not to get too overwhelmed (as Rick Wright cleverly pointed out, the reader is a bit like the aforementioned kingfisher in this regard). The writing is interesting, understandable, often amusing, and even lyrical at times. I don’t like to quote long sections, but I have to include this, one of the most evocative paragraphs I’ve ever read:

Mysterious, romantic, little understood, and seldom seen by the majority of people, the storm petrels are nevertheless among the most abundant and widespread birds in the world. Scarcely the size of a starling, and much, much lighter, they appear to be delicate, fragile things, with their disproportionately long, thin legs and dainty webbed feet. Not so. Storm petrels spend the majority of their existence far from the sight of land, in raging winds and bitterly cold squally seas, in conditions that no other bird of comparable size could tolerate. They find what shelter they need in the troughs of waves and seldom alight on the water’s surface. But they do seem to dance over it, patting the water with their feet, fluttering, hovering, pouncing, and dipping, as they feed on tiny marine organisms disturbed by the turbulence. They are supremely aerial birds, and although they are in many ways the aerodynamic opposite of the albatrosses, their mastery of flight is equally suited to the demands of a totally marine environment.

Doesn’t that just leave you in awe over these seemingly plain birds?

I found very little to criticize here. However, one thing that I found is that the text often mentions special physiological features, especially related to certain bones. Overall, I found it surprisingly easy to pick these out in the accompanying art, but not always. I’d like to see a better visual representation, but I’m not sure of the best way to go about it. I do NOT want to see the existing artwork labeled, which would render it more diagram than art. Perhaps smaller illustrations could be included alongside the text, focusing on the specific features?

Also, this book lacks a glossary. That’s pretty important here so that, for example, when you see an illustration captioned with “Notice the pectinated middle claw”, you can look up the possibly unfamiliar term (another reason why it’s important to read those first chapters).

Recommendation

The Unfeathered Bird is visually arresting and utterly unique. But I had been expecting that. What really surprised me is how much I loved reading it. It’s fascinating, relevant, and will deepen your appreciation for these amazing creatures.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

[…] I used as my source material a picture of a Storm Petrel skeleton from a fabulously beautiful book called The Unfeathered Bird by Katrina van Grouw: wilsons_storm_petrel-unfeathered_bird.jpg (see link for book review http://www.birderslibrary.com/reviews/books/biology_behavior/unfeathered_bird.htm) […]