Reviewed by Grant McCreary on September 22nd, 2012.

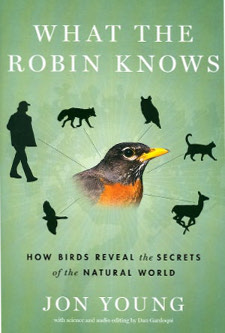

As a birder, I’m always looking for birds and observing how they live. My focus is usually on the bird itself. What species is it? What is it doing? What can I learn about it? But in What the Robin Knows: How Birds Reveal the Secrets of the Natural World, Jon Young urges us to take this a step further and ask what birds can reveal about the world around us.

It turns out, they can reveal quite a bit through their behavior and vocalizations. Young demonstrates that the study of this “deep bird language”, as he calls it, is “the key to understanding both the backyard and the forest”. When you think about this, it shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, as Young writes, “There’s nothing random about birds’ awareness and behavior, because they have too much at stake-life and death.”

So what kind of stuff can you learn? Young spends a great deal of time on bird vocalizations, especially various calls. When I hear a bird call, I immediately consider “What is it?” and “Where is it?” But haven’t you ever wondered what birds are actually saying? Young breaks down vocalizations into five categories – songs, companion calls, territorial aggression, adolescent begging, and alarms – and describes what they mean. For instance, he illustrates the purpose of the companion call with a dramatic story. If you’ve ever been around Northern Cardinals, you’ve undoubtedly heard their chip calls. The author was passing through the territory of a cardinal pair, and the birds were calling back and forth every few seconds. Suddenly, the female didn’t respond, so the male called a bit more urgently. With still no answer, he flew toward where his mate had been. That was when Young saw the female fleeing from a Sharp-shinned Hawk. The hawk was just about to reach her when the male burst onto the scene, flying right between the hawk and its intended prey. The hawk, distracted, swerved toward the male, but it was too late. By then both cardinals had reached cover. Young eloquently sums up the interaction:

I was stunned. This was one of the most powerful scenes involving birds I had ever witnessed. Was it an incredible act of courage, as we would define it? That’s one interpretation, which could be challenged. What can’t be challenged is the lesson I learned about the bond between those two cardinals and the importance of baseline companion calls for maintaining that bond. When the male’s chip went unanswered, his chip-chip asked a question. When the answer was not instantly forthcoming, he took action, and just in the nick of time. The sharpie nearly had the female in its talons before the bright red guy intervened. Almost without a doubt, the “missing” companion call had saved the female cardinal’s life.

The author also maintains that studying this deep bird language can teach you about other animals. Bear with me here a moment. Grab your favorite field guide to mammals. Now check the range map for Long-tailed Weasel. If you’re in the United States, then chances are it’s supposed to live where you are. But for all the time you spend outside birding, have you ever seen one? Me neither. Bad luck? Or maybe the map is wrong? Young has another suggestion. You don’t see a weasel – or a fox, bear, or other retiring animal – because of your attitude. Yes, I know how it sounds. But when the author says that he deduced the presence of weasels around a cottage in Washington based on the behavior of the local birds (later confirmed by finding a weasel nest with young!) when the resident caretaker – a man who had lived there for ten years – said he had never seen one, you get the feeling that Young knows what he’s talking about.

Young describes in detail what you need to do in order to become proficient in deep bird language, based on his years of teaching it. I haven’t put any of his suggestions into practice – I haven’t chosen a “sit spot” and spent the necessary time there. However, for some time I have been sort of following some of the principles espoused in this book. I’m fortunate to live in an older subdivision that includes a ten acre “nature preserve”. It’s not big, nor a bird magnet, but I love it and have found some good birds there. In migration, I try to bird it every morning. But it was a relaxed, unhurried sort of birding. I didn’t usually have any particular target; I just wanted to see what was there. It was a completely different attitude and experience than that of the rest of my birding. Now, I wasn’t nearly as integrated into the environment as What the Robin Knows maintains I can be, but I made an effort not to disturb the birds and wildlife. And I was rewarded with relatively accommodating birds, rabbits that would let me approach, and (I guess when I am particularly in-tune) Barred Owls that would let me glimpse them before they retreated. This book helps to explain not only that, but also why these visits were so fundamentally satisfying. So even if I don’t ever proceed in the study of deep bird language, I’ve got a new framework through which to approach birding, one that may lead to more birds seen and greater satisfaction.

Recommendation

If the idea of studying deep bird language sounds intriguing to you, then you definitely need to read What the Robin Knows: How Birds Reveal the Secrets of the Natural World. But even if it doesn’t, there’s enough practical advice (like how to avoid scaring birds away by your approach) and cool stories (like the cardinals), to make it worth reading.

When I finished reading the book, I was going to leave it at that. But as I’ve been thinking about it in the process of writing this review, I think it’s more than that. Honestly, I don’t know if I’ll ever seriously pursue the study outlined in this book. Even so, it’s already influenced my birding. In the few birding outings I’ve had since reading What the Robin Knows, I’ve had a more relaxed, attentive attitude and noticed things that I would not have before. I’ll stop short of making any sort of grand claim, like “this book has forever changed the way I bird”. That remains to be seen. But it has made an impact and opened my eyes a little. To me, that makes it more than worth reading.

For more information, along with accompanying sound clips, check out the book’s website.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment