Reviewed by Frank Lambert on March 5th, 2012.

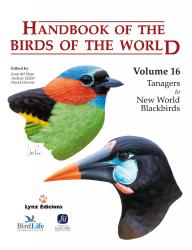

Volume 16 of the Handbook of the Birds of the World covers the last four families of the series, including two of the largest of all, the tanagers (283 species) and the buntings and New World sparrows (326 species), as well as the cardinals and the New World blackbirds, the latter including such spectacular birds as the orioles and oropendolas. Hence the great majority of the species covered are from the New World. As well as marking the end of the series, HBW16 is the last of nine volumes on Passerines, and is accompanied by a plastic-coated reference card which is basically an index to all the families in the last nine volumes.

HBW16 starts with a foreword on Climate Change and Birds, by Anders Pape Møller, an expert in the field. As emphasized by Møller, climate change is probably the most important issue for birds, affecting them on a global scale and in an unprecedented way. The immensity of the predicted effects of climate change is on a scale that defies imagination, yet there are still many people, especially in the USA, who do not believe that climate change is man-made, or prefer to ignore the facts because they impinge on economic forecasts and profit-margins. Unfortunately, this is largely the result of a tiny minority of vociferous climate skeptics with little or no standing in the scientific community at large. The fact is that more than 98% of scientists agree that current changes in climate are a result of man-made changes to the atmosphere due to greenhouse gas emissions. The sooner that everyone understands this, the sooner we can try to deal with the problem. Because if we don’t deal with it, not only is there the possibility that many species may become extinct, but there will be dramatic implications for hundreds of millions of people, especially those living in coastal areas.

The effects of a changing climate on birds is still poorly understood at the individual species level, mainly because research on this topic is new and until very recently few studies had focused on the subject. What is clear is that climate change impacts many aspects of bird behavior and that the responses in one species may be very different to an apparently similar species in the same habitat, or even between different populations of the same species in different locations. Behavioral factors affected by climate change include the start of the breeding season, singing, egg-laying date, clutch size, duration of incubation and nesting periods, the number of clutches, reproductive success, dispersal, the time and duration of spring migration, and even inter-specific competition. Such a complicated and diverse array of effects makes the subject horrendously difficult to study and results are often hard to interpret.

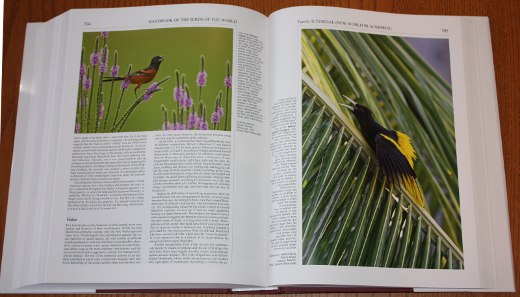

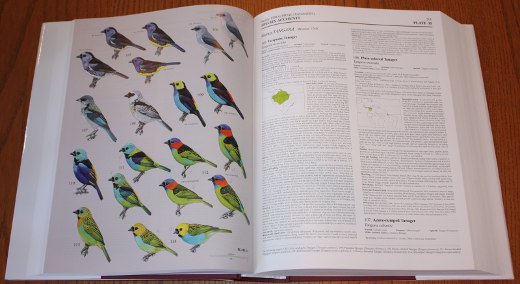

If you can tear your eyes away from the amazing photos, you can learn much and more about these birds just by reading the captions.

Despite the difficulties of the subject, Møller provides the reader with a detailed overview of our current understanding of the effects of our changing climate on birds. But having said this, I have to admit that I came away feeling that we are still a very long way from understanding, much less predicting, what impacts climate change will have on bird populations. Indeed, the foreword raises as many questions as it answers. Although not written in a particularly user-friendly way, being rather scientific and technical throughout, this foreword is nevertheless one of the most important to have appeared in the HBW series, and deserves more than a brief perusal.

Avian systematics is presently undergoing profound changes and revision within families. In particular, the constituent parts of three families included in HBW16 – the Thraupidae (tanagers), Cardinalidae (cardinals), and especially the Emberizidae (buntings and New World sparrows) – are the focus of much debate, revision, and on-going molecular analysis. Numerous recent studies have shown that the traditional classifications so well-known to us all have included a significant number of species in the wrong genera or families. Since a lot of these revelations have occurred during the lifespan of the HBW series many of the required adjustments were impossible to include. Hence, the systematics followed in HBW16 should be treated as provisional, as the taxonomy followed is a traditional one. Nevertheless, the family accounts include considerable discussion of recent molecular analysis and an indication of which genera and species are likely to be moved. This makes for particularly interesting reading.

For example, recent molecular-genetic analysis indicates that the Euphonia and Chlorophonia belong in the family Fringillidae rather than with the tanagers. Neospingus, Chlorospingus, Phaenicophilus, and Spindalis form a monotypic clade that is sister to several New World Warbler genera and are not closely related to other genera treated in the family Thraupidae. Chlorothraupis, Piranga, and Habia may be more closely related to cardinals than to the true tanagers. The longspurs Calcarius and Rhynochophanes, along with Snow and Makay’s Buntings, in the genus Plectophenex may belong in a new family, Calcariidae. A significant number of species here treated as members of the Emberizidae, including the Galapagos finches, may in fact be tanagers. Yellow-shouldered Grosbeak Parkerthraustes humeralis is now known not to belong with the cardinals and is presently placed in incertae sedis (of uncertain taxonomic position). There are many more examples of taxa that may change families in coming years.

At the species level, there are also many splits in this volume. For example, mitochondrial DNA analysis has demonstrated that the “Fox Sparrow” should be split into four species, as has long been proposed, and this treatment is followed by HBW. The fox-sparrows thus recognized are Red iliaca, Sooty unalaschcensis, Thick-billed schistacea, and Slate-colored Fox-sparrows schistacea. Savannah Sparrow Passerculus sandwichensis has also been split, so that there are now three species including Belding’s P. guttatus and Large-billed P. rostratus which are largely confined to Baja California and adjacent California and coastal Mexico. San Benito Sparrow P. sanctorum, is also recognized as a full species by HBW. Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae is split from the Eastern. On the other hand, one species that many may have anticipated being split, Dark-eyed Junco J. hyemalis, has not been. Research has shown that the various races, which form six groups that are sometimes treated as good species, are in fact very closely related to each other, and several races intergrade with each other. Hence, “Oregon”, “Pink-sided”, “White-winged”, “Slate-colored”, “Gray-headed”, and “Red-backed Junco” are all still considered to be races of Dark-sided Junco.

As with all recent volumes of HBW, the standard of all aspects of the book is very high. I was particularly taken by the introductory chapter on the tanagers, which is accompanied by a set of outstanding photographs. Looking at the distribution maps for the 283 species included here in the Thraupidae, I find it noteworthy just how many of these have incredibly restricted ranges. The description of the remarkable diversity of breeding habits shown by the New World Blackbirds is also a fascinating part of this volume. The maps, as usual, seem comprehensive throughout, although no doubt some minor errors have been made – one I noticed is that the map for Greater Yellow-finch Sicalis auriventris (and the text as well) overlooks an isolated population that occurs in Sierra de la Ventana, southern Buenos Aires.

Taken together then, HBW16 is yet another outstanding book from Lynx Editions. It is a fitting end to this wonderful series. In actuality, however, it is not quite the end: in October 2012 Lynx will be publishing a supplemental volume, Special Volume: New Species and Global Index. Apart from an indispensable index covering the entire series, there will be several chapters on changes in macrosystematics and new species described after the publication of their respective HBW volumes, all of which will be illustrated with graphics and photographs. Furthermore, there are plans for the online continuation of the HBW series, as HBW Alive, which will provide the entire contents of HBW at the user’s fingertips for a small subscription fee. HBW Alive will have all of the series’ text, which will be continuously updated by a team of ornithologists, and all of the HBW artwork, which will be viewable in several formats. However, it won’t include photographs, videos, or voice recordings directly on the site itself. For these you will have to consult other sources, such as the Internet Bird Collection, Xeno-canto or the Avian Vocalizations Center.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

You can buy this book in the U.S. from Buteo Books, or elsewhere directly from Lynx Edicions.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

(3 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Comment