Reviewed by Frank Lambert on December 21st, 2009.

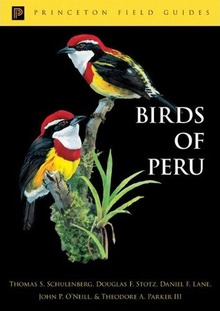

Finally, an accurate, well-organised field guide to the birds of Peru and to one of the richest avifauna’s on the planet! This book is an essential addition to the library of any serious neotropical birder and essential for any visit to Peru, and is a far superior field companion to that of Clements and Shany (2001). With more than 1800 species (1,792 species are covered in this guide), Peru has become a key destination for birding, and many hundreds of birders now visit every year. The book reminds me very much of the Birds of Africa South of the Sahara (Sinclair & Ryan 2003; though it contains a lot more accurate and useful information than the former (rather disappointing) guide. Though it is 656 pages long (with 304 plates), the book’s dimensions mean that it can easily be carried around in the field (it’s smaller and lighter than Ridgely and Greenfield 2001 and Hilty 2003).

The introductory section is typical for a modern guide, with good explanations of how to use the guide, and includes clear maps showing topography, major rivers, the location of protected areas and political units. In the species accounts, each species is portrayed opposite the text and maps. The text includes information on abundance, elevational and distributional information, notes on different subspecies, a description of voice, and sometimes notes on distinctive habits that might have be helpful in field identification. Colours on the maps differentiate between the distributions of residents and both boreal and austral migrants.

The taxonomy that the book uses largely follows that of the South American Classification Committee (SACC), which will not suit everyone, especially those who use Clements, who will find many discrepancies (e.g. splits accepted by Clements such as those for Emerald Toucanet and Rufous-naped Brush-Finch are not followed in this guide). A few other examples where alternative taxonomic treatments exist are: Junin Rail is treated as a subspecies of Black Rail Laterallis jamaicensis (something that will not help conservation efforts on Lake Junin); Puna and Red-backed Hawk are treated as one species, Variable Hawk Buteo polysoma; Willet is not treated as two species; Gould’s Inca is treated as a subspecies of Collared Inca Coeligena torquata; Tschudi’s Woodcreeper is included in Ocellated Woodcreeper Xiphorhynchus ocellatus, Chinchipe Spinetail Synallaxis chinchipensis is treated as a subspecies of Necklaced Spinetail Synallaxis stictothorax; Ecuadorian Trogon is treated as a subspecies of Black-tailed Trogon T. melanurus (and its illustration (upper body only) is tucked away at the corner of the plate, as if an afterthought); Peruvian Tyrannulet is treated as a subspecies of Golden-faced Tyrannulet Zimmerius chrysops, Apurimac Brush-Finch Atlapetes forbesi is treated as a subspecies of Rufous-eared Brush-finch A. rufigenys, which is recognised as a good species by SACC. On the other hand, Kalinowski’s Tinamou Nothoprocta kalinowskii, now known to be Ornate Tinamou N. ornata, has appropriately been left out.

As the previous paragraph suggests, taxonomy is advancing faster in the neotropics than elsewhere, and this is reflected by changes in species limits that have occurred recently. Whilst Clements and Shany mentioned many likely future splits in the text, the new Birds of Peru does not do this in all instances. This is a pity, since the author’s are certainly aware that, for example, Rufous Antpitta Grallaria rufula and Collared Antshrike Sakesphorus bernardi (shumbae race) are very likely to be split into a number of species in the near future. For some taxa, however, the possibility of more than one species being involved is mentioned, as with Tropical Gnatcatcher Polioptila plumbea and Warbling Antbird. Even before this book was published, Warbling Antbird Hypocnemis cantator was split into six species, with two occurring in Peru: Yellow-breasted Warbling-Antbird Hypocnemis subflava and Peruvian Warbling-Antbird H. peruviana (Isler et al. 2007a). The species limits in the genus Percnostola have also been the subject of a recent review, and the taxa in Peru that were previously known as Spot-winged Antbird Percnostola leucostigma are now recognised as two separate species, the southernmost of which is now Brownish-headed Antbird P. brunneiceps.

Unfortunately, the authors have chosen to leave out many species that have recently been discovered, unless they were themselves involved in the discovery. Hence they include Acre Antshrike Thamnophilus divisorius, which was apparently found after their stated cut off date for inclusion in the book (May 2004), but fail to mention other more recently found taxa which one suspects could have been mentioned, such as the undescribed wren and Screech-owl in central Peru, Xenopsaris, Tennessee Warbler Vermivora peregrine (sight record Lago Junin), Lemon-rumped Tanager Ramphocelus icteronotus and Black-cheeked Woodpecker Melanerpes pucherani (Ecuador border in Tumbes). It is, however, more understandable why Bolivian Recurvebill, and Yungus Antwren are not mentioned, since they were first found in Peru in mid-late 2006. Many of these missing species are of course rare, but it seems very odd that they have all been left out completely. The recently described Rufous Twistwing Cnipidectes superrufus, whilst mentioned under Brownish Flycatcher Cnipidectes subbruneus (I much prefer to call it Brownish Twistwing) could easily have been illustrated since it was first recognised as being a good species in 2002. Indeed, all of the recent additions to the Peruvian list could surely have been included by adding a “miscellaneous additional species” plate, as in Ridgely and Greenfield (2001), or alternatively in an additional page of text.

Overall the paintings are of a much higher, more accurate standard than those found in Clements and Shany (2001) though in some of the plates, the yellows and greens seem to be reproduced too brightly. A few illustrations, such as that of Equatorial Graytail Xenerpestes singularis and Short-tailed Finch Idiopsar brachyurus and a number of the hummingbirds don’t really remind me of the birds in the field, but the great majority of illustrations are good to excellent. The paintings of many species are reproduced in large format, something that in some instances gives the impression that the species is large. For example, some of the tapaculos are as large as the thrushes, which could easily mislead first-timers in the neotropics, and even within families, we find a lack of scale. Hence some of the pygmy-tyrants and tody-tyrants and spadebills are larger than or as large as some of the elaenias, Leptopogon flycatchers and Knipolegus tyrants. Tui Parakeet is as large as the Pionus and Amazona species. Some of the chat-tyrants are shown as the same size as bush-tyrants. Pipits are a third to a fifth of the size of the wrens on the following plate. Presumably this problem with scale is a consequence of trying to fit fairly detailed text against the illustrations of the species. In my opinion it has not worked well, and it would have been better to have illustrated more subspecies or variations in plumage (of which many are not shown) to fill in the space, rather than opting to show birds at different scales. Or perhaps it would have been better to follow the format of Steve Hilty’s Birds of Venezuela.

Thirteen artists have contributed their work to Birds of Peru, with their very different styles being apparent. There is a sharp contrast in style and format, for example, when comparing Lawrence McQueen’s beautiful depictions of the various subspecies of barbet on Plate 121 with F.P. Bennett’s illustrations of hermits on Plate 94. McQueen has painted 20 birds representing five species of barbet, whilst Bennett has painted only seven individuals of six species. As a result, the latter plate looks very empty: perhaps the addition of a couple of illustrations of the distinctive nests of hermits could have been used to fill the space, as well as providing something of interest to many users. A final thing that I have to mention is that almost half of Plate 66 is taken up by Rock Pigeon, something I find bizarre considering that many interesting subspecies are not illustrated. Surely a modern field guide should be aiming to depict every subspecies and plumage variation of interest, especially on a continent where significant numbers are being elevated to species level, instead of wasting so space on a domesticated non native species!

In the past, users of the Clements and Shany (2001) field guide had to more or less guess the range of many species, since there were no maps. The maps in this book are therefore a great step forward, The bird distributions are overlaid on a map showing a mixture of some of the main rivers (in the Amazonian region of Loreto) and political boundaries, which is useful, though it might have been better if the rivers could have been drawn in a different colour or form to those lines depicting political boundaries.

Overall, then, this is a great step forward in Peruvian ornithology, and will hopefully stimulate more interest in the birds of this fascinating country. What is needed now, however, is a Spanish version of the book. This would certainly encourage more Peruvians to take an interest in their birds. A Spanish version could also present an opportunity to include the additional species that are fast being discovered throughout Peru!

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

Resources used:

- Clements, J.F. and Shany, N. 2001. A Field Guide to the Birds of Peru. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

- Hilty, S.L. 2003. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

- Isler, M.L, Isler, P. R., Whitney, B.M. and Zimmer, K.J. 2007a. Species limits in the “Schistocichla” complex of Percnostola antbirds (Passeriformes:Thamnophiildae). Auk 119(1): 53-70.

- Isler, M.L, Isler, P. R. and Whitney, B.M. 2007b. Species limits in antbirds (Thamnophiildae): the Warbling Antbird (Hypocnemis cantator) complex. Auk 124(1): 11-28.

- Lane, D.F, Servat, G.P, Valqui, T. and Lambert, F.R. 2007. A distinctive new species of tyrant flycatcher (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae: Cnipidectes) from southeastern Peru. Auk 124(3): 762-772

- Ridgely, R.S. and Greenfield, P.J. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador (Vol 2) A Field Guide. Christopher Helm, London.

- Sinclair, I and Ryan, P. 2003. Birds of Africa South of the Sahara: A Comprehensive Illustrated Field Guide. Struik, South Africa.

A Revised and Updated Edition of this field guide was published in May, 2010.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

A good honest review, however this book should not be completely dismissed because the paintings are awesome double strollers

I have to agree is a great step forward! Wouldn’t mind checking it out the next time I head to Peru for pleasure – zygors guide review

I actually found a spanish version of this book – let me look around and I will be be back! rift blueprint review

Great recommendation. I think I’m sold! Thanks a lot.