Reviewed by Frank Lambert on April 9th, 2011.

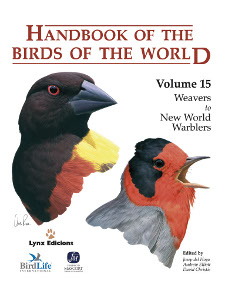

Families covered in this volume are as follows:

- Ploceidae (Weavers)

- Viduidae (Whydahs and Indigobirds)

- Estrildidae (Waxbills)

- Vireonidae (Vireos)

- Fringillidae (Finches)

- Drepanididae (Hawaiian Honeycreepers)

- Peucedramidae (Olive Warbler)

- Parulidae (New World Warblers)

This volume of Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW), the penultimate volume, covers some of the most-studied of all species, and some of the most familiar birds in most parts of the world. But although some of the birds included are very well-known, others are at the other end of the spectrum. For example, Sillem’s Mountain Finch Leucosticte sillemi, is known only from two specimens collected in 1992 on the west Tibetan Plateau at 5,125m, in the practically unexplored Aksai Chin disputed area of China, which is claimed by India.

The book starts with a 55-page foreword on ”Conservation of the world’s birds: the view from 2010” by Stuart Butchart, Nigel Collar, Alison Stattersfield and Leon Bennun, all of whom work in the BirdLife International Secretariat in Cambridge, UK. For anyone interested in bird conservation issues, this essay provides an excellent overview of the status of the world’s birds, the most important pressures they face, and how these threats can be potentially tackled. The review is succinct yet comprehensive, and well worth taking the time to read – the following paragraphs give only a taste of the detail that is packed into it.

Altogether, 1,240 bird species (12.5%) are now threatened with global extinction and 132 species are known to have gone extinct during or since the sixteenth century (and in this respect, the Hawaiian Honeycreepers included in this volume are of particular relevance, with eight recently extinct members of this family illustrated – another eight are illustrated in HBW7). An additional four species, such as Spix’s Macaw Cyanopsitta spixii, are considered to be extinct in the wild (with populations surviving in captivity). Extinctions are continuing: 18 species were lost in the last quarter of the twentieth Century and another three are believed to have disappeared since 2000, including two species from Hawaii (Hawaiian Crow Corvus hawaiiensis and Poo-uli Melamprosops phaeosoma). Furthermore, the authors point out that 13 of the 190 species considered to be Critically Endangered may already be extinct (and hence are tagged as Possibly Extinct in the Wild) and others in this highest threat category will certainly be lost if no targeted conservation action is taken.

The authors provide an excellent, if not rather depressing analysis of the distribution and habitats of threatened bird species, and an analysis of trends (including a reminder that even many of our “common” birds are becoming much rarer) before embarking on a lengthy discussion on the principal threats to birds. These include many that we are all too familiar with, such as agricultural intensification (resulting in habitat destruction and degradation); unsustainable forestry; the spread of invasive alien species and disease (particularly relevant to islands); over-exploitation (hunting and trade, and not forgetting commercial fisheries which are impacting dramatically on many seabirds); and residential and commercial infrastructure development. Other threats that are covered that are perhaps less well understood by the public at large include changes in fire regimes; inappropriate water management, and various types of pollution. The final threat covered is of course one of the most topical, namely climate change.

Whilst the effects of human-induced climate change are debated by some, most of us now accept that increased greenhouse gas emissions are already resulting in slowly increasing temperatures, sea-level rises and shifts in precipitation patterns and snow cover. These changes to our planet are likely to have sweeping and dramatic effects on biodiversity during this Century. Whilst some species may well benefit, for most species climate change will have negative effects through impacts on distribution, abundance, and behaviour. Data compiled by BirdLife International show that climate change impacts have already been documented for 400 bird species, and there are likely many more species that are experiencing effects that we do not yet know about. The essay provides the reader with a brief account of the impacts through known examples before informing us of the likely future impacts of climate change on birds. We learn, for example, that the projected breeding ranges of European species will shift north-eastwards by 260-880km depending on the emission scenario and that on average, future ranges are likely to be 20% smaller than they are now and may only overlap by about 40% with present ranges. This kind of impact will inevitably cause serious problems for many species, in particular those living nearer the poles, and for migrants (which will face longer migrations). Many mountain-top species with limited opportunities for dispersal are also likely to be seriously affected by climate change.

Global warming and sea-level rise will affect not only biodiversity of course, but will surely create profound problems for the next few generations of people on this small planet of ours unless our governments make sincere efforts to tackle the underlying causes. The final part of the forward delves into some of the solutions to the threats faced by birds, under the title of “What can we do?”, and within this 13-page summary many of the actions that our communities and governments should be working to achieve are mentioned. As pointed out by the authors: “Ultimately, biodiversity will only be conserved if enough people care about nature and recognize its importance for human livelihoods and wellbeing, as well as its intrinsic value. Changes in attitudes and approaches are needed at local, regional and global scales among individuals (that’s you and me!), communities, businesses and governments.” The price-tag for improving the status of the world’s threatened species is high, but put into perspective not insurmountable: it is estimated that the cost of saving all the worlds Critically Endangered birds would be less than the sum spent by the USA every four days on the war in Iraq. It seems an incredible fact that this powerful nation can spend so much on armaments and yet almost ignore an extinction crisis on its own soil, where native Hawaiian birds are disappearing at an alarming rate.

The Foreword is followed with the standard approach of HBW that we are now so familiar with. In this volume, three wholly New World families, the Vireos (52 species in 4 genera), Peucedramidae (one species, Olive Warbler Pseucedramus taeniatus) and the New World Warblers (116 species in 25 genera) are covered. African species are also very well represented, with 116 species of weaver in 17 genera, 20 species of whydah’s and indigobirds in two genera; and 134 species of waxbills in 32 genera, of which a significant proportion occur in the Africa and its offshore islands. Other waxbills are widespread in the Asian and Australasian regions (for example munias and mannikins). But the only truly globally widespread family included in HBW15 are the Finches (144 species in 29 genera), with representative species worldwide except for Australia (where some have been introduced), New Zealand (ditto) and most of the Pacific. One endemic Pacific family that is included in this volume are the spectacular Hawaiian Honeycreepers, with 23 species included. Sadly, of these 23, at least 18 are considered to be threatened (and some of these may already be extinct). Another 16 honeycreepers are known to have gone extinct since 1600. The fragility of the honeycreepers is brought home by the photo of the last Poo-uli, sitting in what appears to be a rather small, depressing cage. It died in 2004, and no wild individuals have been seen since that year. Incidentally, the painting of this species on Plate 48 does not look particularly like the photograph in which the bird looks slimmer and longer-billed.

This volume has fewer photographs than the most recent two volumes, 495, compared to an incredible 657 in HBW14 and 546 in HBW13, but as usual the standard of the photos used is excellent. It was somewhat disappointing, however, not to see any photographs of the breath-taking display flights of paradise-whydahs. Regarding illustrations; considering the incredible diversity of nest construction exhibited by weavers, it would have been of great interest to have included a plate or two illustrating these (though to be fair there are eight photos of completed nests).

For most of the families covered, there are few taxonomic surprises, but there is at least one finch that most readers will be unfamiliar with; Corsican Finch Carduelis corsicana (which just made it into Svensson et. al. 2009), as well as one little-known Estrildid Finch, Timor Zebra Finch Taeniopygia guttata (formerly considered conspecific with Australian Zebra Finch T. castanotis), and two New World Warblers, namely Barbuda Warbler Dendroica subita and St Lucia Warbler D. delicata (split from Adelaide’s Warbler Dendroica adelaidae which now becomes a Puerto Rico endemic).

Recent changes in species limits for rosefinches proposed by Rasumussen and Anderton (2005) and Rasmussen (2005) have not been adopted by HBW, although there are good reasons to believe that these splits may be more widely recognised in the future. Hence Himalayan Beautiful Rosefinch Carpodacus pulcherrimus and Chinese Beautiful Rosefinch C. davidianus are still treated as Beautiful Rosefinch C. pulcherrimus; Himalayan White-browed Rosefinch C. thura and Chinese White-browed Rosefinch C. dubius are included in White-browed Rosefinch C. thura; Red-mantled Rosefinch C. rhodochlamys and Blyth’s Rosefinch C. grandis are included in the former species in HBW; Spot-winged Rosefinch C. rodopeplus and Sharpe’s Rosefinch C. verreauxii are included in Spot-winged Rosefinch by HBW; and Caucasian Great Rosefinch C. rubicilla and Spotted Great Rosefinch C. severtzovi are treated by HBW as Great Rosefinch C. rubicilla. Interestingly, the last of these splits has been widely recognised in the past, including by Clement et al. (1993). Apparently the authors believe that for most of these rosefinches, mitochondrial DNA analysis is required before such splits be recognised, which is perhaps surprising considering the species limits adopted by HBW in some other families, such as within the babblers and thrushes, sometimes without such evidence.

Red Crossbills Loxia curvirostra with 19 recognised subspecies ranging across the Palearctic and from Central America to Luzon, Vietnam and North Africa, is still treated as one species. Evidently much more study is required to determine species limits with any certainty, although Scottish Crossbill L. scotica (Great Britain’s only endemic bird), which has been a controversial species since it was first described, is recognised by HBW. In particular, Crossbill taxa in the East Palearctic and Asia are still very poorly-known and we may yet end up with, for example, Philippine Crossbill.

One “taxon” not included in HBW15 is Cream-bellied Munia Lonchura pallidiventer, which gets a mention under Chestnut Munia as “believed to be a hybrid”. This attractive munia was described by Robin Restall (1996a; and see the excellent Plate 70 in Restall 1996b) from a series of nine specimens from the Jakarta bird market that were said to have come from the hinterland of Southeast Kalimantan, Borneo. Although this may well turn out to be a hybrid, I believe that there is the possibility that this is a good species that has just been over-looked.

Some of the bird families covered by HBW15 include many species that have been relatively well studied, and the New World Warblers (Parulidae) are no exception. The introduction to this family runs to 71 pages and the accounts of most species are longer than is typical. The taxonomy followed is fairly standard, but Bachman’s Warbler Vermivora bachmanii is not included since the evidence strongly suggests it is already extinct, though Semper’s Warbler Leucopeza semperi, endemic to the small Caribbean island of St Lucia and which must also be extinct or very close to extinction, is included.

The species limits follow Curson (1994) except for the inclusion of Barbuda Warbler and St Lucia Warbler. Hence, “Audubon’s”, “Myrtle” and “Goldman’s” Warblers are all recognised as being forms of Yellow-rumped Warbler Dendroica coronata. In contrast, however, whilst a small numbers of (knowledgeable) authors have opted to split some of the 43 subspecies of Yellow Warbler Denroicca petechia, HBW15 keeps them all under one species. Robert Ridgely (in Ridgely and Greenfield 2001), for example, recognised Mangrove Warbler D. petechia as separate from migratory northern Yellow Warbler D. aestiva, whilst Steve Hilty (2003) recognised Yellow Warbler D. aestiva, Golden Warbler D. petechia and Mangrove Warbler D. erithachorides. Whilst the illustrations of the New World Warblers appear to be good, they are not comprehensive in that hybrids such as “Brewster’s Warbler” and “Lawrence’s Warbler” are not illustrated (see e.g. Sibley 2000 for illustrations of these).

Within the New World Warblers, a few English names may be unfamiliar, for example, White-rimmed Warbler Basileuterus leucoblepharus is here White-browed Warbler and River Warbler B. rivularis is now Riverbank Warbler. The scientific name adopted for Blue-winged Warbler is Vermvora cyanoptera (not V. Pinus).

As a complement to HBW, and with the ultimate goal of disseminating knowledge about the world’s avifauna, in 2002 Lynx Edicions started the Internet Bird Collection. It is a freely accessible, on-line audiovisual library of the world’s birds where visitors can view or post videos, photos and sound recordings showing a variety of biological aspects (e.g. subspecies, plumages, feeding, breeding, etc.) for every species. The IBC is a very useful source of reference, and currently holds more than 45,000 videos and 32,000 photos representing more than 80% of the world’s species.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

Resources used:

- Clement, P., Harris, A. & Davis J. 1993. Finches and Sparrows. Christopher Helm, London.

- Curson, J., Quinn, D. & Beadle, D. 1994. New World Warblers. Christopher Helm, London.

- Hilty, S. L. 2003. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

- Rasmussen, P.C. 2005. Revised species limits and field identification of Asian rosefinches. BirdingAsia 3: 18-27.

- Rasmussen, P.C. and Anderton, J.C. 2005. Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

- Restall, R. 1996a A proposed new species of munia, genus Lonchura (Estrildidae) Bull. Brit. Orn. Soc. 115: 140-157.

- Restall, R. 1996b. Munias and Mannikins. Pica Press, Mountfield, UK.

- Ridgely, R.S. & Greenfield, P.J. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador. Christopher Helm, London.

- Sibley, D. 2000. The North American Bird Guide. Pica Press, Sussex, UK.

- Svensson, L., Mullarney, K. & Zetterström, D. 2009. Collins Bird Guide: the most complete guide to the birds of Britain and Europe. 2nd Edition. HarperCollins, London.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Comment