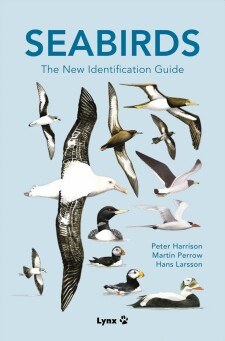

Reviewed by Frank Lambert on October 3rd, 2021.

It has been almost 40 years since Peter Harrison’s classic Seabirds: An Identification Guide was first published (1983; republished with corrections 1985), so this completely updated version of that excellent guide, co-authored with Martin Perrow, will be much welcomed by those interested in seabirds. Our knowledge of seabirds has changed enormously since the 1980s and, in particular, the taxonomy of many seabird groups has been significantly revised. For example, the number of widely recognised tubenoses (albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters, and storm-petrels) has increased from 107 species in 1987 to at least 153 now. Also during this period several excellent field guides have appeared that cover groups of seabirds included in the present book, most notably Oceanic Birds of the World: A Photo Guide (Howell and Zufelt 2018), covering roughly 270 species of oceanic species, as well as handbooks such as Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America (Olsen and Larsson 2003), Gulls of the World (Olsen 2018), and Waterfowl of North America, Europe and Asia (Reeber 2016). Hence seabird enthusiasts are now spoilt for books, and we can soon expect another tome in the form of a comprehensive guide to the tubenoses by Hadoram Shirihai (Bloomsbury).

Seabirds: The New Identification Guide covers 434 species, the majority of which are true seabirds, spending a significant part of their life at sea. These include seaducks (26 species), grebes, sheathbills, phalaropes, skimmers, gulls, terns and noddies, skuas and jaegers, auks, tropicbirds, loons (divers), penguins, albatrosses, southern and northern storm-petrels, petrels, shearwaters and diving petrels (102 species, the largest seabird group), frigatebirds, gannets and boobies, cormorants and shags, and pelicans.

Harrison and Perrow describe ‘seabirds’ as birds that spend part or all of their lives interacting with the ocean, so one might be excused for wondering why the flightless Junin Grebe and Titicaca Grebe, both endemic to lakes in the high Andes, have been included in this guide, whilst other species that one could argue fall within this definition, such as Sanderling, Surfbird, Shore Plover, reef egrets, Scarlet Ibis, Black-faced Spoonbill, and Lava Heron, are excluded. Not surprisingly, Harrison and Perrow have followed the principle set out in Seabirds (1983) by including all species in each group (except ducks) even if some rarely or never get to sea.

This was a slightly odd decision in 1983, and I find it rather disappointing that no changes were made regarding what has been included in the guide 38 years later. Indeed, Seabirds makes an obvious exception to his rule by including three phalaropes but no other waders (shorebirds). Surely it would have been better to leave out those species that never get to the sea, like the two grebes mentioned above, and other species that only use marine environments rarely, like River Tern, Black-bellied Tern, and Spot-billed Pelican, or skimmers, which visit the coast seasonally, just like the numerous species of shorebird that are excluded. Clearly it is a difficult proposition to produce a book on a suite of birds that cannot easily be defined, but the result of covering so many species is that the product is large and heavy.

Whilst this book is undoubtedly an identification guide, the layout and size preclude its use in the field as a guide that can be quickly consulted, and whilst invaluable on occasions when it is possible to carry it around, one suspects that most seabird enthusiasts will likely refer to Oceanic Birds of the World on a pelagic trip when actively trying to identify any “ocean” bird that has just been seen. That is presumably why the first edition of Seabirds was followed by the concise Seabirds of the World: A Photographic Guide (Harrison 1987), a guide that could easily be carried around in a large pocket. Seabirds: The New Identification Guide is therefore best treated as a reference book, which is perhaps what it is intended as by the authors.

With the book running to 600 pages, the introduction is rather brief, relating almost exclusively to the identification of the species in the guide, rather than including anything much about breeding biology, feeding behaviour, conservation, etc. Instead, it focuses on giving some brief but pertinent advice about seabird identification, with paragraphs on jizz, habits, size, moult timings, and plumage details. The section on How to Use this Book includes useful guidance on ageing terminology as well as an essential glossary of terms and illustrations of seabird topography. It also includes a set of maps that show the location of the many islands used by seabirds, as well as the location of Oceans and Seas, some of which are less widely known. These island groups are replicated on maps inside both front and back covers of the book, which seems like overkill, and it would perhaps have been better to have had a succinct plate/page guide inside one cover.

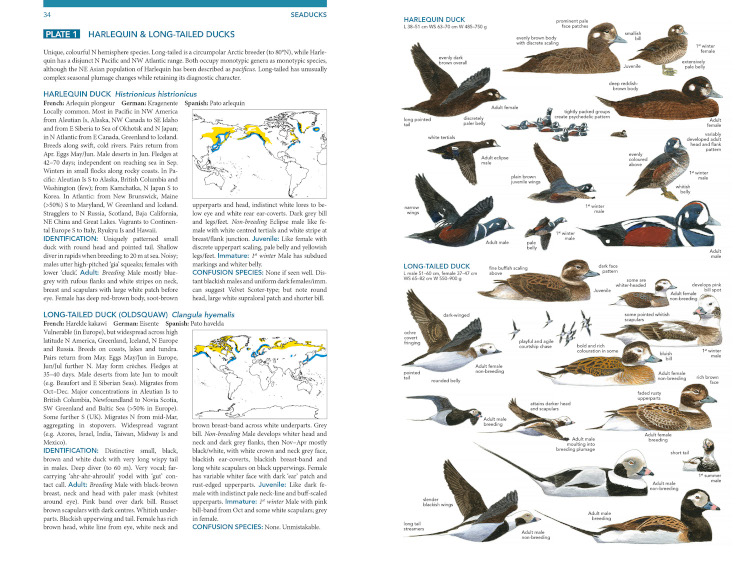

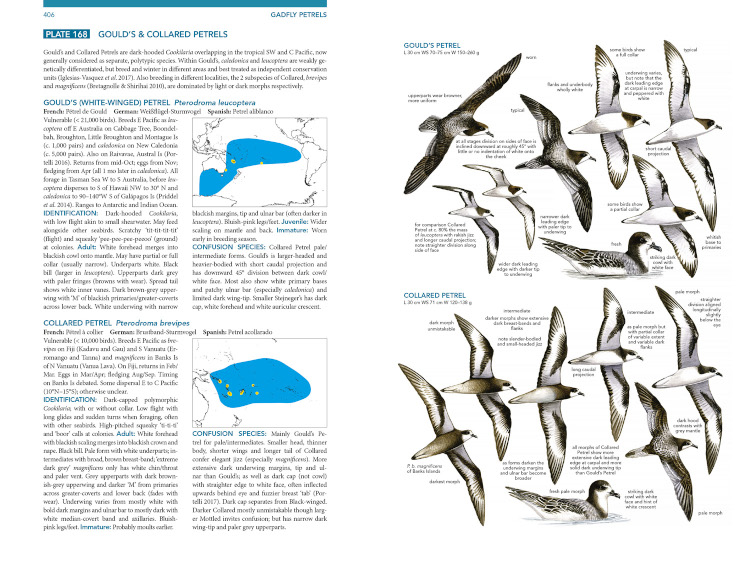

The bulk of the book, some 540 pages, is the “Systematic Section”. This comprises a section for each of the bird groups included (listed above), starting with an overview of the group, again primarily focusing on the main features that can be used to identify and distinguish the various taxa. Each species is illustrated opposite its species account, these including a colour distribution map and a succinct description of distribution and movements, plus a few words on breeding habits and, usually, a short section on confusion species. For most species, the species account takes up half a page of text and half a page of illustrations, but there are full page accounts for species with more variation in plumages, such as many of the larger gulls, skuas, and some of the albatrosses. Occasionally, three species are included on a single page and plate (e.g. phalaropes, some murrelets, grebes, and rockhopper penguins).

There is a large amount of small text on the plates to assist with key identification features, but I found this rather distracting, as is the inclusion of similar species that are inserted on plates without clear delineation, which can be misleading if glancing at the plate without reading all the fine print. Unusually for a book by a major publisher, an unfortunate error was made with Plate Six, illustrating Black and Common Scoter. Labelling on the plate is mostly misplaced, but a corrected version of this plate can be downloaded from the Lynx website (Errata page).

Although Peter Harrison painted most of the plates for this guide, those of the gulls, terns, skimmers, skuas, and seaducks (138 of 434 species) are meticulously and beautifully illustrated by Hans Larsson. It is a pity that Larsson was not also commissioned to paint some of the other groups, since Harrison’s paintings of some of the auks, petrels, shearwaters, diving-petrels, and grebes are not particularly pleasing. Harrison has a distinctive style in which he tends to place unusual emphasis on feathering, which can distract from the overall plumage details in some cases. Nevertheless, illustrating and co-writing the text of any bird guide is an incredible accomplishment, and whilst some of Harrison’s artwork is not as good as that of many professional bird artists, it is certainly a remarkable achievement to have illustrated so many species in so many plumages. In total, the book includes more than 3,800 individual figures on 239 plates, an incredible accomplishment by any measure.

From comparing photos of seabirds with the illustrations in this new guide, one can certainly discover differences and minor inaccuracies, although most of these simply reflect variations in plumage. Others, however, reflect real inaccuracies. From Harrison’s paintings of Bulwer’s and Jouanin’s Petrels, for example, one could get the impression that a stepped tail was an identification feature of the latter, which it is not, and that both species have very prominent, pale, visible quills to the flight feathers, something not supported by photos. Another example is that the dark bars on Fulmar Prions painted by Harrison seem too bold when compared to photos. Yet another is that photos of both Black-browed and Campbell’s Albatrosses tend to show pinker-looking bills than illustrated, whilst the black eye-patch of Campbells tends to look bolder and longer than illustrated by Harrison.

The distribution maps that are incorporated within the species accounts, opposite the paintings, are colour-coded to show where a species is likely to occur when breeding, when not breeding, and where a species is resident. Of course, seabirds regularly range outside of their normal distribution, but no attempt has been made to define vagrancy on the maps, which could have caused confusion, although vagrancy is detailed in the text. One thing that would have been useful would have been to label maps to indicate when particular pelagic species are breeding, and when they are mostly encountered away from their breeding sites. This could have been accomplished with the simple addition of numbers for the various months. Whilst this information is outlined in the text, having it on maps where it is feasible to include it would have been helpful because not every reader will be familiar with the location of the island groups, seas, etc that are mentioned.

The species texts start with details of distribution and include the odd snippets of ecological data such as dates of egg laying and incubation time, or a mention of diet, but this varies from species to species. For most species, half the text is devoted to Identification, with a separate section on Confusion Species where relevant. Confusion species are, however, necessarily restricted to those species that are likely to occur sympatrically.

The taxonomy of many seabirds remains incompletely resolved, and no recent bird guide will satisfy everyone with regards to the taxonomy followed. In Seabirds: The New Identification Guide, I noticed that Gibson’s Albatross (Diomedea gibsoni in Howell and Zufelt) is treated as a subspecies of Wandering Albatross D. exulans, although it has its own account and set of illustrations. Albatrosses still provide a taxonomic challenge, whilst another example is provided by the diving-petrels, and whilst Harrison and Perrow mention that the population of South Georgia Diving-petrel that breeds on Codfish Island, New Zealand is now considered a species it is not illustrated, and as noted by Howell and Zufelt it is not identifiable in the field. IOC, meanwhile, still treat this taxon as a subspecies. Another difference with some taxonomies is that Seabirds does not recognise the split of European Storm-Petrel into British and Mediterranean, recognised by Howell and Zufelt but not yet by IOC.

A more serious failing here is that no attempt has been made to describe the six likely cryptic species of Band-rumped Storm Petrels. Instead, Seabirds concentrates on the differences between Band-rumped and other recognised similar taxa. In contrast, Howell and Zufelt provide a set of photos for each form and all the known information that might be useful in differentiating them at sea. Furthermore, whilst Howell and Zufelt provisionally recognise six species in the White-bellied Storm-Petrel complex, Harrison only recognises one, Titan Storm-Petrel, and the five taxa that remain lumped are illustrated with only 7 individuals, compared to 22 individual photos in Howell and Zufelt, who tease out the often-subtle differences using carefully selected images accompanied by succinct text.

Overall, the treatment of Storm-Petrels in Seabirds is probably the weakest of all the seabird groups. Sidestepping the likely potential splits within this complex set of taxa means that there are fewer maps and fewer illustrations, as well as less information on likely distinguishing features of closely related taxa, resulting in more confusion as to which taxa might be expected in any particular region of the ocean. This is perhaps a missed opportunity on the authors’ part, and it is a shame that they didn’t include full species accounts or more detailed information for those taxa that are presently suspected of being good species, some of which will almost certainly be elevated to species level within the next decade. One has the impression that Harrison is perhaps not so comfortable with storm-petrel identification, but to be fair, this applies to almost everyone I know.

Despite first impressions that some illustrations are not so pleasing, Seabirds: The New Identification Guide is another excellent bird guide from Lynx. It is the sort of book that would be indispensable to have on any major pelagic trip, and a useful reference guide at home. I doubt it will always be the first book that seabird aficionados will turn to. But for the many birders that prefer paintings to photos this guide is especially recommended since there is presently nothing to compare it with that illustrates so many forms of so many species with paintings. I will certainly pack it for my next pelagic trip with WildWings.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

(2 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Comment